- Illegal logging persists deep in the heart of Cambodia’s Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary amid government inaction and even complicity with the loggers.

- Routine patrols by local activists and community members have painstakingly documented the site of each logged tree in the supposedly protected area, even as these community patrols have been banned by the authorities.

- Mongabay reporters joined one of these patrols in April, where a run-in with rangers underscored complaints that the authorities crack down harder on those seeking to protect the forest than on those destroying it.

- A government official denied that the logging was driven by commercial interests, despite evidence to the contrary, instead blaming local communities for cutting down trees to build homes.

PREAH VIHEAR, Cambodia — Sometime after 10 a.m. on Friday, April 21, sweat poured down the face of veteran environmental activist San Mala as he crawled through the forest undergrowth, some 16 kilometers (10 miles) deep in the heart of Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary in northern Cambodia.

Rangers from the Ministry of Environment were closing in and were calling out for the activists to give themselves up.

The rangers had appeared as the camp of community patrollers Mala had accompanied were preparing breakfast. Mala and a handful of his team were already in the forest and managed to escape. Now, the activists were dragging themselves through the foliage as silently as they could.

Footsteps crunched close and the rangers’ walkie-talkies crackled unseen through the thick greenery. The humidity and the fear of arrest made for a heady mix, but Mala remained calm. This was not his first flight from the authorities while trying to defend Cambodia’s forests.

Mala turned and silently ordered the group to stop. He held his finger to his lips, gesturing at Mongabay reporters, who had joined him and the Prey Preah Roka Community Network — a grassroots activism group comprised of volunteers from communities near the wildlife sanctuary — on one of their patrols through the protected forest to gather data on illegal logging.

Insects swarmed over the team as they crawled on their stomachs in the dense undergrowth, trying to stay as low as possible while following a stream that would lead them around the camp where yet more rangers, armed with rifles, were waiting.

They had no food or water, no phone reception, and all of their vehicles and equipment had been left at the camp as they fled. They also had no idea what had happened to the rest of the community network members.

Now the activists had a difficult choice: It was 13 km (8 mi) to the northern border of the protected area, 20 km (12 mi) to the eastern border and 16 km to the southern border, all through dense jungle, intense heat, and with armed rangers in hot pursuit.

Cambodia’s persecuted protectors of the forest

Two days earlier, on the evening of April 19, Mala arrived in a village just outside Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary. There, he met 12 members of Prey Preah Roka Community Network to prepare for what was supposed to be a three-day patrol in the protected forest.

Almost a decade of experience has taught Mala the need for discretion, and he avoids entering the wildlife sanctuary in daylight so that authorities are less likely to see his face.

“We know the authorities here and they know us,” Mala said before setting off on patrol. “Some are friendly, they understand our mission, but mostly when we see them, we have to run into the forest and hide.”

What Mala describes as his “mission” has consisted of working with mostly Indigenous communities to organize forest patrols and gather data on illegal logging by collecting the coordinates of freshly felled trees, and then helping the community publish its findings on social media.

Mala’s own Facebook account has some 41,000 followers at the time of writing and he frequently finds a large audience by shining a light on the destruction across what is now a 347,568-hectare (858,859-acre) protected forest in the northern province of Preah Vihear, close to the Thai and Laotian borders.

Prior to August 2023, the Preah Roka and Chhaeb wildlife sanctuaries were two separate protected areas, spanning some 90,000 and 190,000 hectares (222,400 and 469,500 acres) respectively, but they have since been merged and absorbed additional land in an environment ministry-led shakeup of Cambodia’s protected area system.

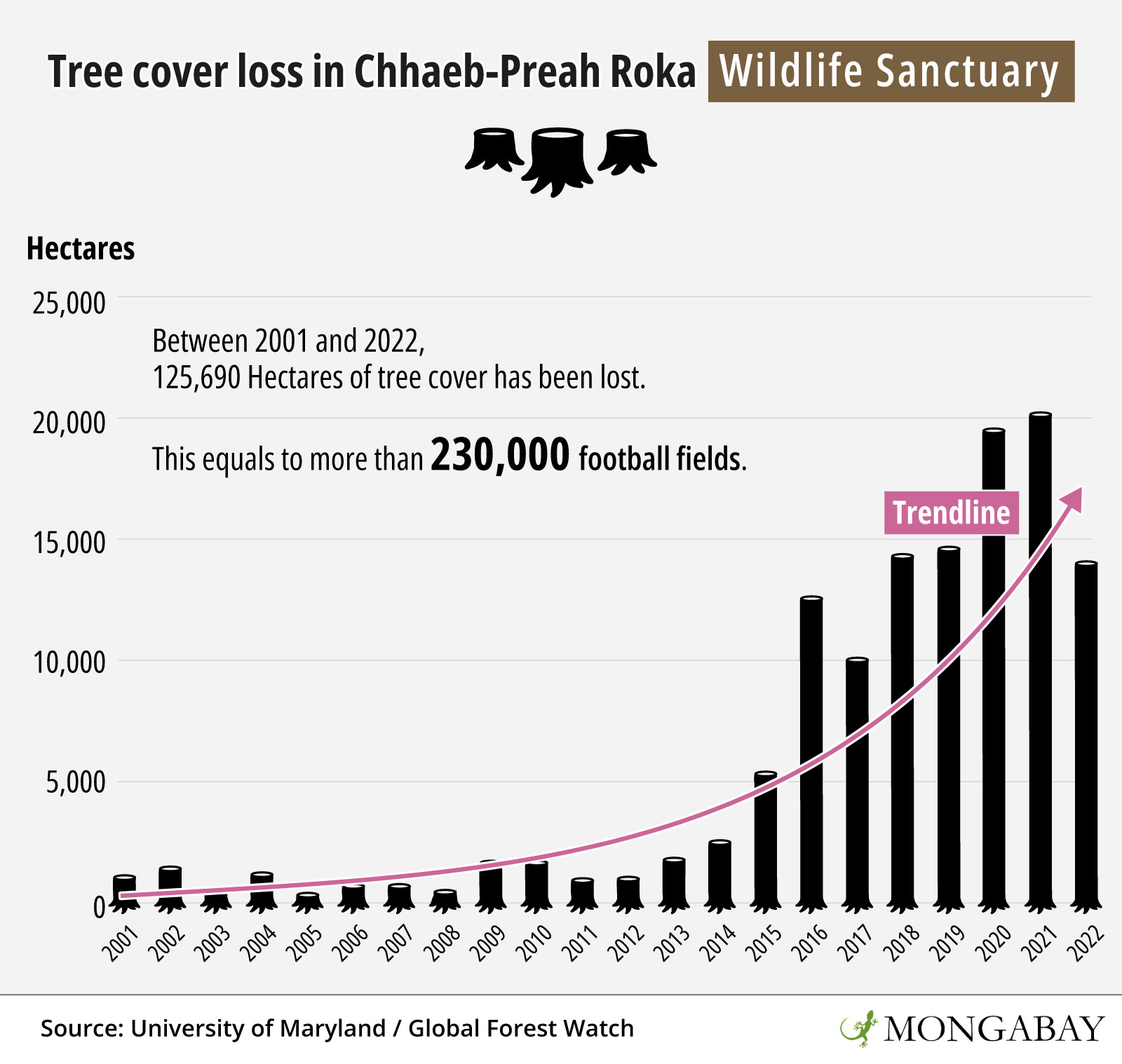

Yet despite its protected status, Chhaeb-Preah Roka lost 31,600 hectares (78,100 acres) of tree cover between 2001 and 2022, according to Global Forest Watch data. But this may be an underestimate, according to data gathered on the ground by the Prey Preah Roka Community Network, which has uncovered a more egregious pattern of deforestation.

Exposing the scale of the forest loss in Chhaeb-Preah Roka has placed Mala and the community in the crosshairs of the Cambodian authorities, while forest crimes continue unabated.

“We used to come on patrols here with Ministry of Environment rangers, but that stopped in early 2020 when the government outlawed community patrols in Preah Roka and Prey Lang,” Mala said. In February that year, Cambodia’s Ministry of Environment deemed community patrols illegal unless the community had formed an NGO that was registered with the Ministry of Interior.

“Now, when we see loggers, all we can do is film them and report it. Before, when we patrolled with government rangers, we could arrest them.”

Following the logging routes

After rumbling for hours through the night in a convoy of koy-yun — long, four-wheeled tractors adapted for use in thick forests and on rough terrain — Mala and the 12 community members who joined him for the patrol made their camp around midnight. The patrol team bathed in a nearby stream, cooling off amid the oppressive humidity before stringing hammocks between trees.

Rainy season had not yet arrived and the prickly heat rose with the morning sun. It remained a constant throughout the day, as did the remains of freshly felled trees that brought the convoy to a halt as community activists documented each one, collecting GPS coordinates and measuring the width of hewn tree stumps.

Flies buzzed around Sokhun, a member of the community patrol who requested to use a pseudonym to avoid repercussions from authorities, as he crouched over a stump with a tape measure. This one measured 90 centimeters (35 inches) in diameter.

For four years now, Sokhun has joined the patrols throughout Chhaeb-Preah Roka where he has helped map out the path of destruction that loggers have cut through the protected forest. In April, he came across hollowed-out carcasses of trees, mostly koki (Hopea odorata) and cheuteal (Dipterocarpus alatus), both of which are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, as well as kakoh (Sindora siamensis). But Sokhun identified this new stump as phdeak (Anisoptera costata), an endangered species that he said is rapidly vanishing from the forest.

Loggers use chainsaws to carve out a cuboid center of the largest trees, taking only the most valuable parts while leaving behind a trail of fallen remains.

“They likely took around 0.7 cubic meters [25 cubic feet] from this tree, but it’s valuable — around 800,000 Khmer riel [roughly $190] per cubic meter,” he said.

These square logs are easier to stack on the koy-yun used by loggers as well as to transport via truck once out of the forest, he added, noting that loggers try to make each trip as cost-effective as possible.

The carved-up remains make it easier for the patrollers to track the loggers, but Sokhun’s task is seemingly unending under the brutal afternoon sun. The bone-rattling journey into the heart of Chhaeb-Preah Roka is punctuated only by the discovery of yet another freshly cut stump.

Each clearing tends to be connected, often by a narrow path of flattened undergrowth as loggers move from one valuable tree to another. Like following rat tunnels to the nest, Sokhun, Mala and the rest of the community split up to cover more ground in the 43° Celsius (109° Fahrenheit) heat.

“You can see the impact of the ban on community patrols,” Sokhun said as he cross-referenced the coordinates of a tree stump against existing data gathered by the community. “After the ban in 2020, we saw more illegal logging, both in Preah Roka and Prey Lang. I think maybe 40% of Preah Roka has been illegally cut down in the last three years. Maybe in another three years it will all be gone.”

Legally gray

Sokhun usually leads these patrols twice a month during the dry season; in the wet season, even the koy-yun struggle to churn through the mud, meaning the forest is usually at its safest when the rain is heaviest. Rain or shine, though, every patrol yields more stumps, more data and — increasingly — more danger.

“We have experienced confrontations with loggers armed with axes and knives. All we can do is try to document it on camera,” he said. “Sometimes, local officials tell loggers which days to avoid coming into the forest so they avoid being caught, but the soldiers, police and rangers will work day and night to catch activists in the forest. They all take money from the loggers.”

Cambodia’s 2008 Protected Areas Law lays out four distinct management zones: These range from the core zone of a protected area — which is illegal to enter without permission from the Ministry of Environment — to conservation, sustainable use, and community zones, with varying levels of access granted to the public for each.

But no zonation was ever completed for either Chhaeb or Preah Roka wildlife sanctuaries, nor has it been done since the Ministry of Environment merged the two into Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary. From a legal standpoint, all 347,568 hectares of the newly formed protected area could be considered off-limits to the public. However, the 2019 census data show that 13 villages exist within the boundaries of the protected area, while a further 18 sit on its borders.

When contacted in September, Phay Bunchoeun, spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment, said the ministry’s rangers cooperate with community members who wish to patrol the forest, but noted that only community organizations that have signed contracts with the ministry are able to participate.

“As for the annual loss of forest, as mentioned above it is not true,” Bunchoeun said when presented Global Forest Watch data that show a spike in tree cover loss across Chhaeb-Preah Roka in 2020 and 2021 following the ban on the Prey Preah Roka Community Network’s patrols.

Instead, Bunchoeun said, the destruction was the result of farmers living within the protected area, and not commercial logging operations.

“Communities still demand trees to build houses for local people from confiscated trees in protected areas in accordance with the community’s agreements with the Ministry of Environment, but it is not [due to] any business activities,” Bunchoeun said.

He added that in the past three months, ministry rangers had conducted 230 patrols in Chhaeb-Preah Roka and found 105 cases of natural resource crimes, confiscating 49 chainsaws and sending three individuals to court.

“A large number of perpetrators who have been cracked down on in the past have been sentenced to prison and have not been released to date,” Bunchoeun said.

Sweet deals

But all of the available data point to a more recent spike in deforestation across Chhaeb-Preah Roka.

The area lost around 5,220 hectares (12,900 acres) of tree cover between 2001 and 2015, Global Forest Watch data show.

Then, from 2016, the rate of loss accelerated more than fivefold.

In the same year, Hengfu Sugar Group, a Chinese company, inaugurated its $360 million sugar mill and refinery on the southern border of what was then Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary.

The company skirted Cambodian regulations limiting each concession to 10,000 hectares (24,700 acres) per company by simply creating five subsidiaries, each winning a concession spanning between 6,000 and 9,000 hectares (14,800 and 22,200 acres), bringing the total to 42,422 hectares (104,827 acres). All five companies were awarded their concessions on the same day — Nov. 8, 2011 — and a Hengfu representative told Chinese state media in 2016 that “the company has been granted land covering an area of 424.22 square kilometers.”

These sugar concessions opened up logging routes along roughly 56 km (35 mi) of Chhaeb-Preah Roka’s border, while simultaneously displacing local communities and robbing them of arable land, forcing many to seek in an income logging in the forest.

Capitalizing on this development, Dy Duk, a tycoon well-known in Cambodia’s logging business, was granted rights by the Forestry Administration to operate a sawmill in the concession belonging to Rui Feng, one of the Hengfu subsidiaries. From 2017 onward, Duk was repeatedly accused of illegal logging in what is now Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary. His sawmill was shut down in February 2018, only to reopen with an even wider jurisdiction: Duk’s company, Sam Oeun Sovann, was in September 2018 granted rights to logging across all five of the Chinese sugar concessions.

Duk’s sawmill was last known to be operating in mid-2019, but the company could not be reached by contact details listed in the Ministry of Commerce’s records as the phone numbers have since been disconnected. Calls to numbers listed on the company’s website and elsewhere online also went unanswered.

Neither Dith Tina, the minister of agriculture, forestry and fisheries, who pledged to review inactive economic land concessions in March 2023, nor his spokesperson, Im Rachna, responded to multiple calls, messages between March and September or written questions submitted by Mongabay in June.

Bunchoeun of the Ministry of Environment said that there was no sawmill currently operating within the sugar plantation concessions.

The timber baron network

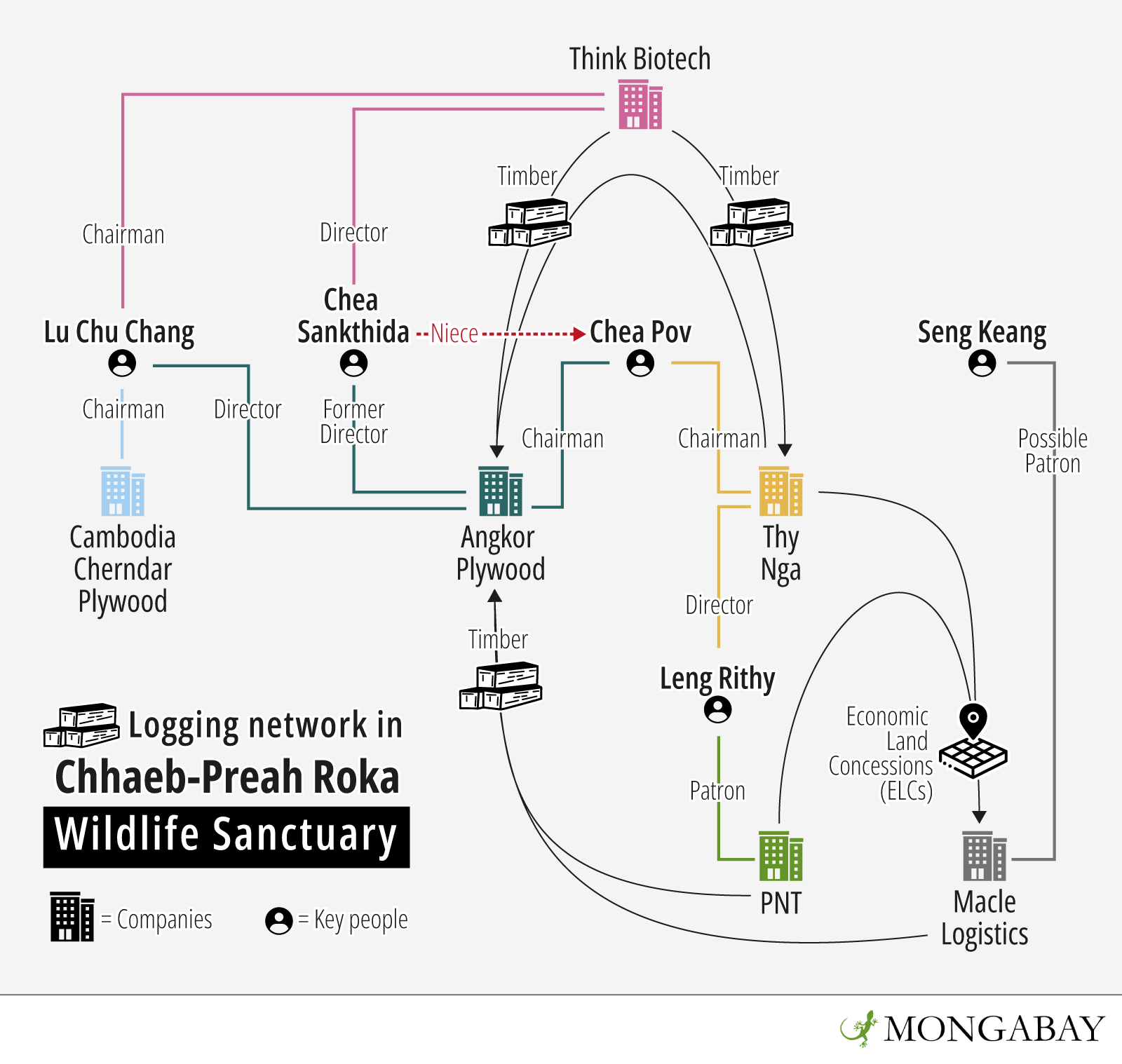

While logging dominated the sugar plantations in this part of the protected area’s borders, some 40 km (25 mi) further south two Vietnamese rubber plantations, PNT and Thy Nga, were established in 2011. They would go on to establish a similar pattern of deforestation.

No rubber trees were ever planted, but PNT and Thy Nga gutted the supply of commercially viable timber from inside their concessions, as well as beyond their borders — including timber alleged to have been harvested illegally from both Prey Lang and Preah Roka. The two firms worked together to further pick the borders of Preah Roka and Prey Lang clean of valuable timber, until Macle Logistics, another company, took over both concessions in December 2017.

In 2018, Cambodia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries granted Macle Logistics licenses to harvest and transport timber from inside the former PNT and Thy Nga concessions, even though the nearly 14,000-hectare (34,600-acre) concessions had already been cleared of all commercial timber by the former concessionaires. Timber kept flowing, which analysts have suggested indicates Macle Logistics was sourcing timber illegally from inside Chhaeb-Preah Roka and Prey Lang.

Earlier this year, loggers reportedly working for Macle Logistics protested an apparent lack of payment from the company after having illegally harvested timber from the section of Prey Lang that sits within Preah Vihear province, just south of Chhaeb-Preah Roka.

Macle Logistics has previously been identified as transporting timber to Angkor Plywood, a prominent Cambodian logging firm that has faced repeated allegations of illegal logging, mostly in Prey Lang.

Chea Pov, chair of Angkor Plywood, is also listed as the chair at Thy Nga, and works extensively with Lu Chu Chang, a director at Angkor Plywood and chair of Think Biotech, which has been proven, extensively, to be illegally logging in Prey Lang since he took over in December 2018. Chang runs Think Biotech with Pov’s niece, Chea Sankthida.

Chang has been logging in what would become Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary since 1996, when one of his previous ventures, Cambodia Cherndar Plywood, won a 103,300-hectare (255,300-acre) forest concession.

When interviewed by Mongabay in June, Chang confirmed that he operated Cherndar, but denied that he had ever engaged in illegal logging in either Chhaeb-Preah Roka or Prey Lang.

Uniformed loggers

Many forest concessionaires paid for protection or logistical support from the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) — themselves a prominent faction in Cambodia’s timber trade, who since the ’90s exploited the proximity of Chhaeb-Preah Roka’s forest to national borders and reportedly had ample opportunity to engage in illegal logging.

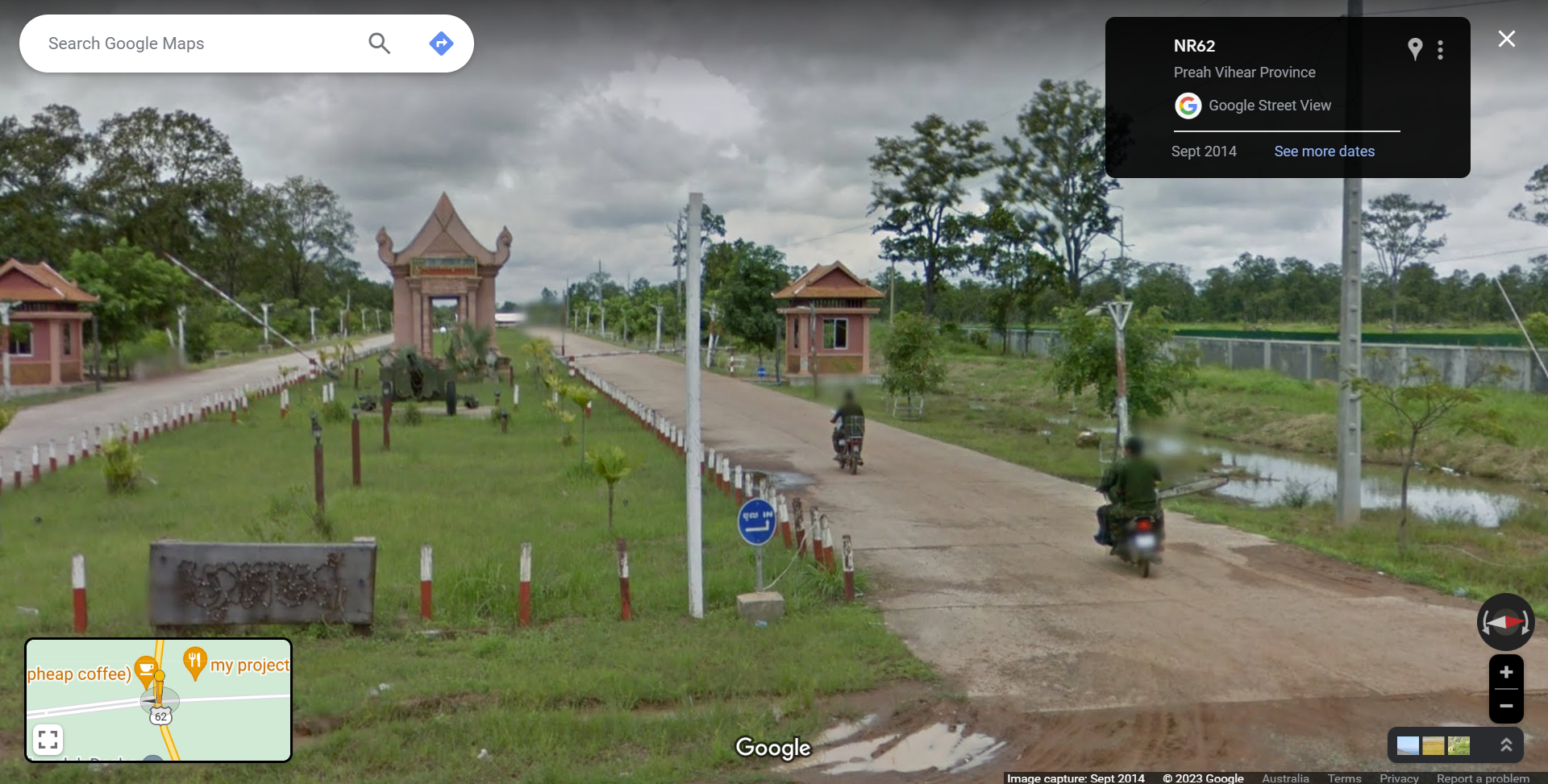

Soldiers from one outpost in the area, Military Intervention Division 3, were so frequently involved in logging in the area that a soldier returning to base with a chainsaw strapped to his back can be seen during a September 2014 visit from the Google Maps Street View car, which has only visited Cambodia twice.

Kim Rithy, the governor of Preah Vihear province, whose father, Kun Kim, was a prominent figure in the RCAF, did not respond when sent questions regarding the ongoing destruction in Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary, the harassment of activists, or the apparent impunity afforded to loggers.

“Even police officers or soldiers in the nearby Tbaeng Mean Chey district, they are also involved because we understand that officials get money from [forest] criminals,” Sokhun said in an interview with Mongabay during the community patrol of Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary.

“It looks like it’s not a protected forest, it’s a forest for their businesses,” he said of the various factions involved in the destruction of the forest. “And we know [the government has] a lot of officials, but they are lacking a willingness to protect the forest.”

Loggers roam free as activists detained

The consequences of this can be seen while traveling through the protected forest.

For the first night and much of the first day that Mongabay reporters were there, the forest encountered was badly degraded and scarcely looked worth protecting; shrubby, skinny trees protruded from ground bearing the scars of well-worn logging tracks.

The forest thickened out as the patrol pushed deeper into Chhaeb-Preah Roka on April 20, when Mala, Sokhun and the community documented 28 separate incidents of illegal logging. A previous patrol in March, one that was uninterrupted by authorities, uncovered 198 new stumps, up from the 40 incidents recorded in a January patrol.

Patrols in October 2022 and August 2022 produced 79 and 258 illegal logging data points respectively.

But even 16 km from the southern border of the protected area, the patrol came across an abandoned logging camp, which is where they set up for the night of April 20.

“We’ve had reports from local communities that loggers come this far into the forest,” Mala said. “They take the most valuable timber and they sell it back to the concession near Prey Lang.”

The concession Mala referred to is the Macle Logistics concession, some 40 km from Chhaeb-Preah Roka.

On April 21, the second morning of the community patrol in Chhaeb-Preah Roka, Mongabay reporters used a drone to identify six new clearings within the forest. But the patrol would have no time to investigate these new clearings or any potential connections to Macle Logistics.

As reporters interviewed Mala a short walk away from the camp, armed Ministry of Environment rangers arrived at the camp and detained everyone who didn’t run immediately.

“We have to escape, we have to hide,” said Mala, who has already served time in prison for his activism. “If they see us, they will catch us and throw us out of the forest.”

After fleeing and hiding for more than an hour, the activists and community members who had not been detained decided that the safest route back would be to surrender to the rangers — but not before contacting various rights NGOs in Phnom Penh when phone service became available in the forest.

At this point, it was unclear if Mala, Sokhun, the community members or the Mongabay reporting team would be arrested or face legal action from the Ministry of Environment. Rangers told Mala that the entire patrol would be taken back to Preah Vihear’s provincial capital, handed over to the police and likely transferred to the courts for entering the protected forest without permission.

The three rangers ordered the activists into their koy-yun and escorted the convoy for a tense three-hour journey back out of Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary.

Upon crossing the border of the protected area, the rangers spoke with their superiors over the radio; while nobody was able to ascertain the details discussed, all those present in the patrol team were told they were free to go, but that they were banned from the forest.

Reporters have since learned that a coordinated intervention was made on behalf of the activists and community network members by a number of rights organizations in Cambodia.

However, the mounting pressure applied to the activists’ ad-hoc conservation tactics saw the patrols come to a halt in the run-up to and aftermath of the July 2023 elections. By early September, though, the community’s convoy of koy-yun had once more taken to the forest of Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary, tracking the trail of the loggers who had gone before them.

Banner image: The carved up remains of a tree in the supposedly protected Chhaeb-Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary seen in April 2023. Image by Andy Ball / Mongabay.