- Billions of cubic meters of Mekong River water are now harnessed behind dams in the interests of power generation, severely affecting crucial physical and biological processes that sustain the river’s capacity to support life.

- As the pace of hydropower development continues to pick up across the river basin, cracks in the region’s dated and limited river governance systems are increasingly exposed.

- Major challenges include the lack of formal, legally binding regulations that govern development projects with transboundary impacts, and a legacy of poor engagement with riverside communities who stand to lose the most due to the effects of dams.

- Experts say that open and honest dialogue between dam developers and operators is needed to restore the river’s natural seasonal flow and ensure the river’s vitality and capacity to support biodiversity and natural resources is sustained.

This is the second article in a Mongabay series focused on changes to the ecology and hydrology of the Mekong River. Read Part One.

Niwat Roykaew, an environmental activist based in Chiang Rai province in northern Thailand, described the Mekong as a naga, a mythical water serpent and symbol of fertility that brings abundance to the entire region.

The river, which flows across the borders of six countries, supports a vast array of ecosystems, irrigates farmlands with nutrient-laden floodwaters, transports stabilizing sediments downstream, and nourishes world-renowned fish populations that form the basis of much of the region’s food security. The river is also a vital part of the traditions and cultural practices of the people who live alongside it. But, Niwat said, a relentless procession of dam building has inflicted wound after wound on this ancient, but suffering, life force.

“The river, as a living creature, feeds the people of the Mekong, but this naga is being slashed to pieces and its power diminished,” he told Mongabay.

As the rate of hydropower development in the region continues to build in response to the global drive toward decarbonization, cracks in the region’s dated and limited river governance mechanisms are becoming ever more apparent. The competing interests of six countries, paired with a mindset that often prioritizes profit above protecting ecosystems and livelihoods downstream, has left a legacy of unilateral and piecemeal decision-making, creating enormous challenges for the watercourse and all who depend on it.

Decision-makers now face the reality of managing a struggling river system increasingly impacted by the cumulative effects of successive hydropower projects, along with other threats such as rampant deforestation, overfishing, and an ever-shorter rainy season due to climate change.

“We cannot relax,” Anoulak Kittikhoun, CEO of the Mekong River Commission Secretariat (MRC), an intergovernmental agency that fosters dialogue between the four countries of the Mekong’s lower basin, said in a speech delivered in 2022. “Our feet should be on fire — we need to act.”

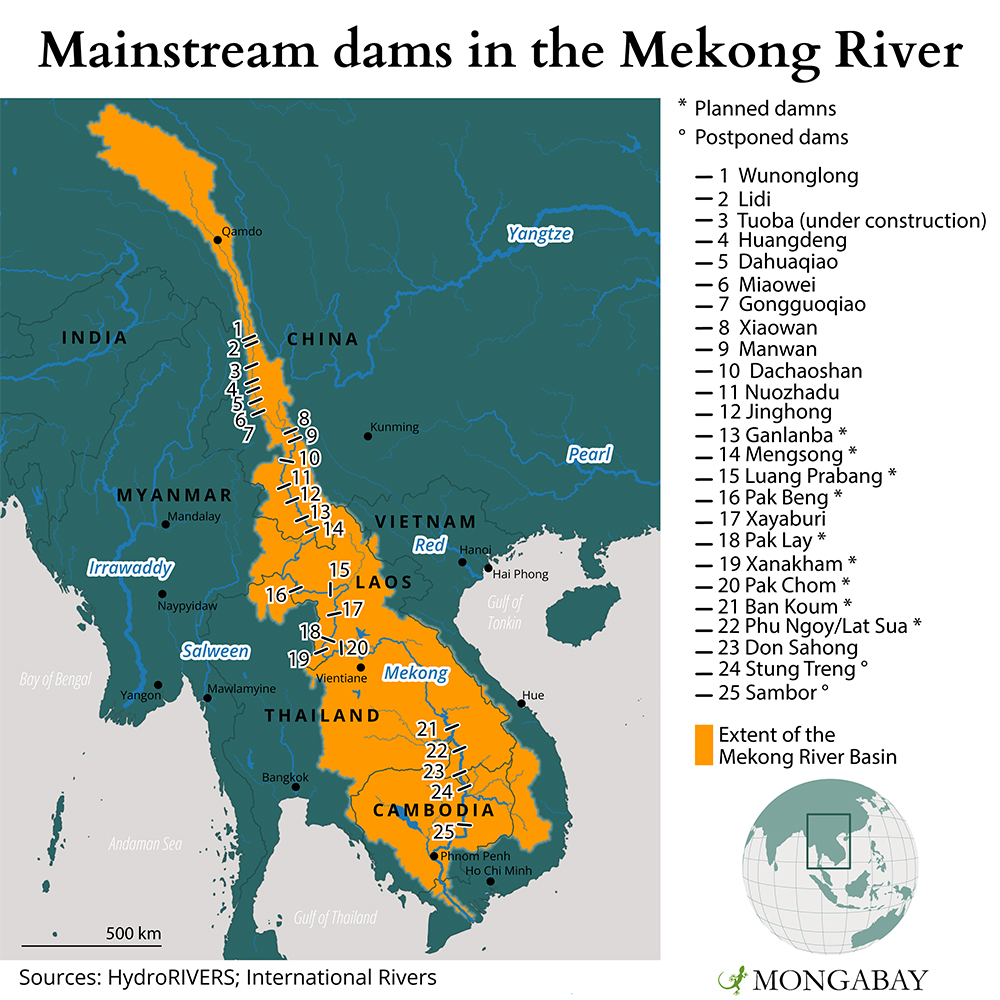

More than 160 hydropower dams have been built along the river and its tributaries since the 1960s. Crucially, the pace of damming the wide and muddy mainstream river channel, home to critically endangered freshwater dolphins and the world’s largest freshwater fish, shows no sign of abating.

A total of 13 dams span the Mekong’s mainstream — 11 in China and two in Laos. Eight further mainstream projects are either planned or under construction in China, and nine are in various stages of planning in Laos and Cambodia, the latter largely motivated by the prospect of selling energy to regional neighbors like Malaysia and Singapore.

With billions of cubic meters of the river’s water now in storage reservoirs, key processes that shore up the functioning of the entire river system are buckling under pressure.

Dams sever fish migration routes and natural sediment transport pathways, and monitoring initiatives have found that hydropower projects have “inexorably” altered the river’s natural seasonal ebb and flow. The modification of this ancient rhythm alongside which ecosystems and riverside communities have evolved is dramatically changing the landscape and ways of life in the river basin, manifested in the form of dying ecosystems, dwindling fish catches, and riverbank erosion.

Compounding the development pressure, fishing and farming communities living downstream have endured failed monsoon rains and droughts in recent years that have brought water flows to their lowest ever recorded levels in parts of the lower basin, decimating their livelihoods.

More questions than answers

With their natural resource base depleted year after year, downstream riverside communities who bear the costs of upstream dams are demanding answers from the region’s leaders for why so many dams are required in the first place.

Development pressure is systematically undermining the integrity of the whole river system, according to Niwat, the environmental activist. Awarded the Goldman Environment Prize in 2022 in recognition of his advocacy to safeguard the river from plans to channelize the Mekong by blasting away a section of river rapids that serve as valuable fishing grounds, Niwat said he can’t rest on his laurels. The same stretch of river in Chiang Rai province is again threatened by a dam under consideration in neighboring Laos.

The northernmost of the nine megadams slated to be built on the mainstream river in the lower basin, the 912-megawatt Pak Beng project is situated roughly 100 kilometers (60 miles) downstream of the Thailand-Laos border. The backwater from the dam is projected to affect upstream river levels, flooding vital farmland and orchards. It could also potentially affect valuable fisheries species, according to a technical review of the project. Nonetheless, at a press briefing in October 2022, local authorities said they had no definitive information on the likely impacts of the project.

At the meeting, local fisherman Chaiwat Duangpida expressed his concern about the planned development, pointing out that livelihoods are already undermined in the area due to impacts on water levels from the cascade of dams upstream in China. “What am I going to do?” he asked. “Living is very difficult if there is a dam.”

Despite the concerning lack of information and inadequate environmental impact assessment, activists say the Pak Beng project is building momentum, with pivotal steps in the planning process for the dam steadily proceeding.

One-way consultation

Riverside communities and environmental activists say they’re not being heard through the decision-making process when it comes to hydropower projects, especially those situated in neighboring countries. Instead, they say they’re largely left in the dark, which makes it challenging to predict how developments will affect their ways of life.

Transboundary development decisions are largely governed via set of regulations through the MRC, based around the 1995 Mekong Agreement between the four lower basin countries of Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, with China and Myanmar as dialogue partners. However, the rules aren’t legally binding, and neither the MRC nor any national government has the powers to veto any projects on the river, even those deemed harmful to the river and its resources.

Due to these limitations, dams have typically been constructed on a project-by-project basis with national-level decisions taking precedence. The Mekong Agreement stipulates that countries should notify neighbors of any mainstream projects, but tributary projects can proceed with very little international discussion, paving the way for potentially devastating projects like the heavily criticized Sekong A dam, to be built largely without discussion of the environmental, social or economic consequences.

Even for mainstream dams, for which the MRC requires a six-month public consultation process, communities have little opportunity to meaningfully affect the planning process, said Ormbun Thipsuna from the Thai Mekong People’s Network from Eight Provinces, a community group that has campaigned against dams for more than a decade.

“We have the opportunity to go to consultation meetings with the four lower basin country representatives,” Ormbun told Mongabay. “But the government representatives just listen to us. They cannot prevent the dams from happening [in other countries], they just say ‘OK, we listen, but we won’t do anything.’ Ultimately, the developers are just thinking about budgets, profits and business. They don’t think about people or the environment, just business money.”

Teerapong Pomun, director of Thailand-based nonprofit Living Rivers Association, agreed that public consultations don’t sufficiently bridge the gap between decision-makers and the local communities who stand to lose the most due to dams. As a result, he said, many riverside communities are disillusioned with what they perceive as a rubber-stamp procedure on a done deal. And without national or international legislation to protect the river, communities feel disempowered to effect real change.

“It’s a very poor process that never takes the voices of local people and stakeholders to the decision-makers,” he said. “The authorities that came to talk [at public consultation hearings] just came to promote the dams, and they didn’t have enough knowledge to answer questions … They often didn’t invite villagers or [civil society organizations] who oppose the dams, they just invited people who live far from the Mekong, who won’t be impacted much.”

Mainstream dams proceed despite evidence

The first test of the Mekong Agreement to govern mainstream dam building came in 2010, when the government of Laos brought the 1,285 MW Xayaburi dam project before the Mekong River Commission. The project immediately garnered skepticism from the downstream governments of Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, and strong opposition from impacted communities and environmental groups who criticized its environmental impact assessment for failing to consider transboundary impacts.

The lack of consensus spurred several rounds of technical evaluations by independent consultants and the MRC, the findings of which overwhelmingly recommended a moratorium on mainstream damming in the lower basin for at least a decade.

One 2011 study that took account of ecosystem services and fisheries losses concluded that although Laos would derive an economic benefit from its mainstream dams, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam would all suffer respective financial net losses of $129 billion, $110 billion and $50 billion. Another study, published in 2017, calculated that the river’s wild capture fisheries, valued at $11 billion per year, would suffer yield losses of 40-80%, resulting in disproportionate impacts on rural poor households.

Various groups, including the MRC and UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, have subsequently found serious shortcomings in the social and environmental impact assessments for the slew of mainstream dams proposed since the Xayaburi project went into operation. Criticisms have included outdated and plagiarized sections of environmental assessments and inadequate assessment of cultural heritage impacts.

Despite the wealth of evidence cautioning against mainstream projects, developers and national governments continue to invest in and drive forward hydropower in many parts of the lower basin, with Vietnamese and Thai construction companies and banks involved in many projects in Laos that will result in downstream impacts within their borders.

Experts caution that additional mainstream dams scheduled for construction simply aren’t needed to meet the region’s energy needs. Thailand, for instance, has a “massive” oversupply of electricity, according to Gary Lee, Southeast Asia director at International Rivers. The Thai Ministry of Energy reportedly announced in early 2020 an energy reserve margin of 40%, equal to around 18,000 MW, which is more than the combined capacity of all 11 existing and proposed mainstream dams in the lower basin, according to the Save the Mekong Coalition.

“Instead of building more large dams that benefit the few at the expense of millions in the Mekong, we need to prioritize more sustainable and equitable energy options and pathways, which respect the rights of communities,” Lee told Mongabay. “To do this, we need to listen to the voices — and respect the rights — of people who live along the river, and who have been most impacted by large dams.”

Without meaningful engagement and fully considering the opinions of affected communities, little will change, said Teerapong from the Living Rivers Association. “Government ministers who are on the Mekong River Commission Council do not use the concerns of local communities to negotiate or talk with other countries,” he said. “The MRC just does the studies, but they cannot make the decisions.”

‘A lot can be done’

Ian Baird, a professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the U.S., has studied changes in the Mekong’s lower basin for several decades. What’s most needed now, he told Mongabay, is an open and honest discussion between dam operators about how to manage existing dams in such a way that they benefit the river and its people, while continuing to fulfill a real need for power generation.

Shifting the operating schedules of large-capacity dams in particular could help to restore a semblance of the river’s natural flow regime, Baird said. “These are fundamental things that we know are going to have positive impacts — there’s a lot that can be done,” he said, but added that such a shift would require dam developers and operators to change their mindsets away from profit maximization toward a wider view that considers the health and livelihoods of those living downstream.

Such a move calls for elevated levels of transparency and circular sharing of knowledge between developers and local communities. This would not only enable investors to make better-informed decisions about the ethical implications of the dams they’re financing, but would also clarify the ultimate purpose of the dams to those affected downstream.

With China sharing more data than ever on water levels within its borders through the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism (LMC), progress toward this end is being made. Launched in 2016, the LMC seeks to cooperate with the MRC through a series of agreements and joint study commitments to find out more about the hydrological and fisheries health of the whole river.

But high-level diplomatic cooperation and technical studies don’t necessarily translate into meaningful policy-level action that will help riverside communities who stand to lose the most due to dam impacts, according to Carl Middleton, a political scientist at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand. There’s still a long way to go before impacted communities are fully integrated into the decision-making process, he said.

“Tensions can emerge [because] community movements see the river not just as something to be managed for economic development and scientifically managed sustainability, but also as part of their sociocultural practices,” Middleton told Mongabay.

Faced with the prevailing paucity of information on planned dams and a lack of formal, legally binding mechanisms to protect the river and its resources, communities are taking matters into their own hands through the formation of the Mekong People’s Forum. The new forum seeks to “build up a civil society mechanism to balance the power in the Mekong,” Teerapong said, and to elevate community voices from the ground up.

Given the shrinking civic space in many parts of the Mekong region, those working in Thailand, where concerns can be raised more openly than in Cambodia, Laos or Vietnam, say they feel like they represent everyone in downstream dam-affected countries. “We have to carry the beacon for the whole river,” said Ormbun from the Thai Mekong People’s Network from Eight Provinces. “We represent the voices of silenced communities in other countries.”

Respect for the river’s intrinsic value

Back in northern Thailand, Niwat said people operating boats and tending riverside gardens must check for updates on water levels on a daily basis to ensure they’re not caught unawares by sudden fluctuations caused by upstream dams.

Gazing directly across the river to Laos and the jetty that accommodates the boat that sails tourists downstream to the World Heritage Site at Luang Prabang, Niwat said people here continue to live in limbo, not knowing when or why the dams will come to change their lives forever.

When the dams upstream in China came into operation more than a decade ago, sandbar islands began to form in the middle of the river here. More than 20 now exist, many of which are fully vegetated and have given rise to debate between villagers from Laos and Thailand over who has the rights to use them for grazing and fishing. These sorts of disputes will only intensify up and down the river if the suite of planned mainstream dams is built in the lower basin, Niwat said.

Rather than focusing on high-level diplomacy, Niwat said, river governance bodies like the MRC should be advocating a new vision for the Mekong: one that isn’t centered around hydropower, but takes full account of the fact that the river is a living being. As Niwat described it, the river is a timeless, ancient life force that delivers blessings to the people of the entire region.

When asked about what he perceives as an appropriate mechanism to hold companies and governments accountable and responsible for damages to the river, its resources and associated livelihoods, Niwat acknowledged the need for financial compensation, but cautioned against solely viewing the river in terms of its monetary worth.

“We must not lose sight of the river’s intrinsic value,” he said. “People are losing much more than just money and income. They’re losing a way of living, a way of life. What about the ecological value and other aquatic life and other ecosystem values? We need to think about those values too.”

For Niwat, the focus must now be on the monumental task of restoring the entire river system to its former vibrancy of life. “If we ignore the need to heal the river itself, then we will lose all of the river’s natural resources forever.”

Banner image: The water in Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia, is channeled from Mekong and its tributary during the flooding season. Image by Carolyn Cowan/Mongabay.

Carolyn Cowan is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @CarolynCowan11

Read Part One:

As hydropower dams quell the Mekong’s life force, what are the costs?

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.