- Mongabay’s Liz Kimbrough spoke with documentary filmmaker Ken Burns about his upcoming documentary, “The American Buffalo,” which premieres in mid-October.

- The buffalo was nearly driven to extinction in the late 1800s, with the population declining from more than 30 million to less than 1,000, devastating Native American tribes who depended on the buffalo as their main source of food, shelter, clothing and more.

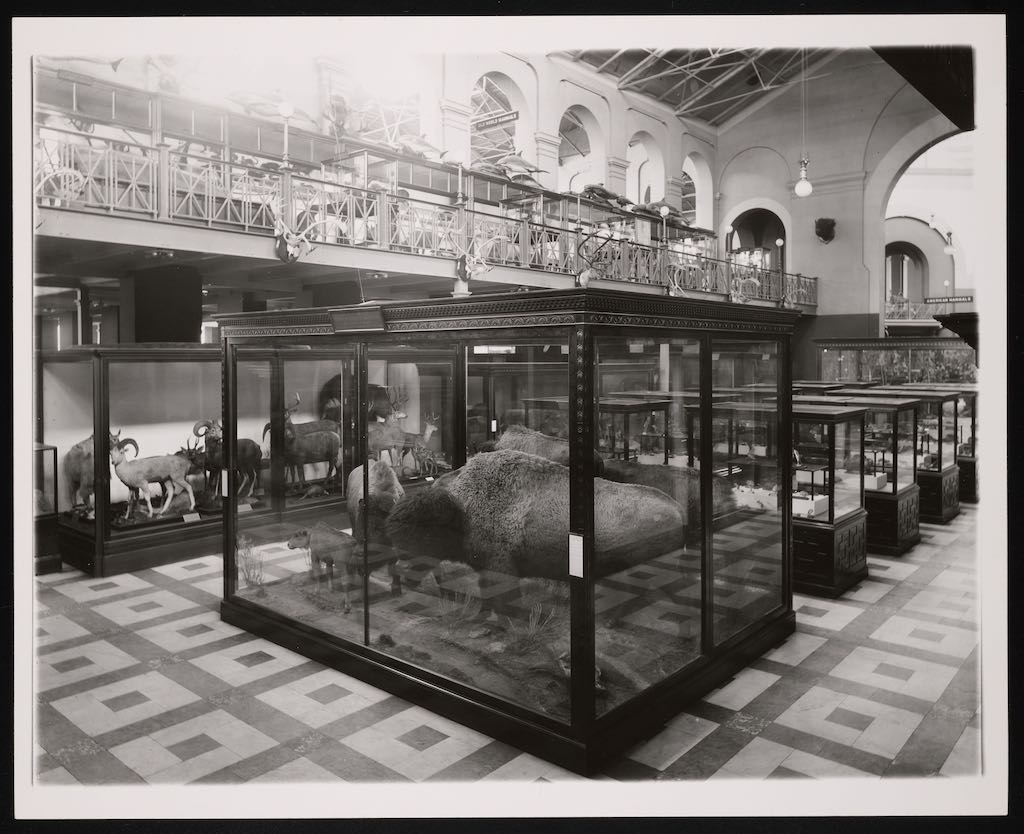

- The film explores both the tragic near-extinction of the buffalo as well as the story of how conservation efforts brought the species back from the brink.

- Burns sees lessons in the buffalo’s story for current conservation efforts, as we face climate change and a new era of mass extinction.

Award-winning filmmaker Ken Burns tells stories that shed light on the complexities and nuances of the United States’ cultural tapestry. This time, Burns has turned his lens on a symbol of the vast North American plains: the American buffalo (Bison bison).

In a poignant discussion with Mongabay’s Liz Kimbrough, Burns delves deep into his upcoming two-part documentary, The American Buffalo, set to premiere Oct. 16 and 17 on PBS, the U.S. Public Broadcasting Service.

The documentary navigates the harrowing journey of the American bison, one that historian Rosalyn LaPier describes as two distinct tales. One is a chronicle of the intimate relationship shared between Indigenous communities and the buffalo; a bond nurtured over millennia. The other is the darker story of the buffalo’s near-annihilation at the hands of European settlers and the subsequent Americans.

These settlers, driven by cash bounties for buffalo hides, decimated the buffalo population, causing it to plummet from a staggering 30 million to less than 1,000 within a few decades. This massacre spelled calamity for the Indigenous tribes, whose existence was intertwined with the buffalo.

In what Burns views as a concerted effort, this annihilation not only targeted the buffalo but symbolized the larger intention of bringing Native Americans to their knees.

“What was most disturbing and heartbreaking was not just the slaughter of the animal, which in and of itself is beyond the pale. But the idea that behind it … sometimes verbalized but never written into real official policy, was the realization that ‘if we kill the buffalo, we kill the Indian’,” Burns told Mongabay.

Burns said his team insisted on Indigenous participation and representation during the filmmaking. The documentary includes interviews with scholars, land experts, and members of many tribal nations.

The story of the bison is one of utter heartbreak, but also hope. The documentary’s second installment celebrates the diverse ‘motley crew’ of people who snatched the species from the jaws of extinction. Today, the U.S. is home to approximately 350,000 buffalo, descendants of less than 100 animals.

“So, there’s this incredible dimension of tragedy but also uplift that have to be taken in the same breath,” Burns said. “It also has to be acknowledged that this is what the human predicament is.”

The American Buffalo premieres Oct. 16 and 17 on PBS. Its release will be accompanied by educational materials for middle and high school students available at the Ken Burns in the Classroom site.

The following interview transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity. To hear this conversation with Ken Burns via Mongabay’s podcast instead, click play here:

Mongabay: What brought you to the buffalo, and why did you decide to tell this story?

Ken Burns: Well, over the decades, we’ve been dealing with the physicality of the American West. In the mid-90s, we made a series on the history of the West. We did the story of Lewis and Clark. We did a history of the national parks. All of them were the story of the buffalo. We just wanted to do it.

I’m so glad we waited the several decades it took because we have a lot more scholarship and a lot more sense of what’s happened. There have been deeper dives. We’ve also, I think, as filmmakers and as a culture, learned even if our sympathies are with another point of view, not just to pay them some lip service, that it might be possible for me as a filmmaker, for us as a film team, to be able to yield to other points of view and present a very complex story.

In a way, the two parts [of the documentary], one would be a kind of Inferno, like Dante’s Inferno, and the other would be a Paradisio, this parable of de-extinction. But as we got deeper into the film, it’s much more than that.

In some ways, we’re just the first two acts of a three-act play. As citizens of the United States, but also of the world, we are responsible for writing the final act. And that has to do with addressing climate change. It has to do with rescuing species or rescuing ecosystems and habitats that would permit those species to return along with all the other species or all the other flora that have been driven out of places like the great plains of the United States, which was called, and was, the American Serengeti.

There are so many other implications and so many other perspectives that I’m glad we waited. And I’m very proud of the film, and I’m thrilled that you enjoyed it.

Mongabay: This film covers not only the near-extinction of the buffalo but also the genocide of Native people. How did you ensure accurate and adequate Native representation and participation in the film?

Ken Burns: Well, we insisted that there be [Native representation]. Our consulting producer, Julianna Brannum, is [a member of the Quahada band of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma]. Many of our advisers were Native people. Some of the people involved in the work of [buffalo] restoration now are Native people that we interviewed, and that populate our film. And so I think what you hear is not just our voice, but other voices and other perspectives that helped to kind of, in the best possible way, disrupt presumptions we have about the American narrative.

We told the story of how inextricably intertwined Native populations were with this most noble of beasts, our national mammal, not just the symbol of the West, but the national mammal now. These are people that have 600 generations of experience with this animal, and the white European population at best has six or seven, in terms of the United States. And so what was most disturbing and heartbreaking was not just the slaughter of the animal, which in and of itself is beyond the pale. But the idea that, behind it, sometimes unspoken, sometimes verbalized, never written into real official policy, was the realization that if we kill the buffalo, we kill the Indian. We tame the Indian. We deprive them of the principal sustenance of those tribes on the Great Plains that had used everything from the tail to the snout of this animal, and incorporated the sounds of the animal into its rituals, and used its waste on the nearly treeless plains to fuel fires.

And then you see the wanton buffaloes being killed early on in the 19th century, 30 million, we think, at the beginning of the 19th century; probably 60 million leading up to that. By the mid-1800s, there were 12-15 million. We don’t have any accurate way to count them. And by the end of the 1880s, no one can find one. And your 1,000 figure includes all those in private collections, little zoos and places like that, and a couple of Native reservations. So, you really see a species on the brink of extinction.

But you also see the entire vibrant life, over 12,000 years of Native peoples being extinguished. And their connection, which is not just physical but often spiritual, and in terms of these people’s basic origin stories, creation myths, and lifeways, is severed and broken. And it’s only now that we’re beginning to glimpse a reconnection, which is startlingly poignant and sad to see because people who look like us are responsible for that genocide of people and their ways and the near-extinction of this beautiful mammal. It’s a really tragic story, and fortunately, it ends positively, or at least hands it over to the rest of us to figure out what we will do now that it’s not in danger of going extinct. What does that actually mean? To save it? Is that really it? Or are there other responsibilities that we have?

Mongabay: Several sources in the film speak to the unwritten, but not unspoken, policy of the United States government and military to drive Indigenous people onto reservations by eradicating their source of life, liberty and spirituality.

Ken Burns: And I think another thing, too, is that when you look at the people who were so-called benevolent progressives interested in Indians, they created Indian schools. Their slogan was, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” They cut off their hair; they dressed them in Western dress; they beat them if they spoke their native tongue. And so there is a real kind of cultural genocide that’s going on if it isn’t a complete genocide of the population. There are wars, and there are deliberate massacres and killings. But it’s disease and hopelessness of being confined to a reservation and the taking away of this principal, symbolic part of their lives, that is at the heart of the tragedy.

So the story of the buffalo is intertwined with the story of Native Americans and intertwined with all of us, too. We’re culpable in every way. The United States is sort of proud of this manifest destiny. In order to have that manifest destiny, at least 300 individual nations had to be either destroyed or confined to reservations.

Mongabay: These large mammals are such an important part of the ecosystem. As people are moving toward regenerative agriculture and rewilding as solutions to address climate change (we know so much of the climate crisis is caused by agriculture and issues with the soil), bringing these animals back seems to be an important part of our national solution to addressing these issues.

Ken Burns: I agree. There’s a kind of silence now on the Great Plains. It’s a monoculture of one or two plant species cultivated in agriculture. The deer and the antelope are still there, to some extent, but grizzly bears, elks, and the bison that were there have fled to their own refuges, if they have them, up into the Rocky Mountains. There was this magnificent expanse that had untold numbers of species as well as flora. You don’t want a monoculture. You don’t want one or two species of plants; you want something else. And that, in turn, invites people back, and you have the kind of Eden our ancestors felt this was as they approached it. But their idea of relating to this Eden was to be its master, tamer, and controller. Whereas the Native American ethos was to be part of it, that the animals were relations. Wallace Stegner, we quote him at the beginning of our second episode, says that man is the most dangerous species on Earth and every other species, including the Earth, has reason to fear it. But we’re also the only species, if we wish to, that can save another species.

So, there’s this incredible dimension of tragedy but also uplift that has to be taken in the same breath. It also has to be acknowledged that this is what the human predicament is. We are destroyers; we look at beautiful rivers and think dams; we look at stands of trees and think board feet; we look at remarkable canyons and wonder what minerals can be extracted. And yet, we’re the same creatures, Americans are the same people who created national parks. The idea is that everyone, for all time, not just the rich or royalty, could own the most spectacular places on the planet. That’s also part of us.

Mongabay: The film tells the stories of individuals who had a role in protecting and bringing back the buffalo. Some decided to keep a few buffalo and raise them in small private herds that served as the breeding stock for reintroducing the species. Tell me about these small, individual stories and what we can learn from them.

Ken Burns: A lot of people were saving buffaloes, not necessarily for the right reasons. Many people got involved in the conservation movement who were very much a part of white supremacy. Many of them subscribed to the pseudoscience of eugenics that suggests a hierarchy of races, ethnicities, and even nationalities, which is, of course, bunk. There’s only one race, and that’s the human race. So you find an odd, but at the same time, very familiar motley crew of people, like Molly Goodnight, lonely on her ranch in the panhandle of Texas. Her husband spent his life killing Indians and then killing buffalo to make room for his cattle. And they begin to raise some at her bidding. Then, he softens and changes his relationship to both the buffalo and the Native Americans.

Fred DePuy and Good Elk Woman in the northern plains are saving buffalo. People in New Hampshire, where I live, had a big herd. There are buffalo in the zoos. There were buffalo alive, wild and free. But just a handful, maybe a couple dozen, in Yellowstone National Park. But what all of those individuals suddenly realized, particularly the scientists among them, is that a lightning strike or a disease could destroy buffalo, and what was needed was federal involvement. In fact, the feds came through, having not only created Yellowstone National Park but then began, through the efforts of Theodore Roosevelt, wildlife refuges beginning in the Wichita Mountain in what is now Oklahoma. Here, the Kiowa Indians believe the original buffalo came out and returned when we hadn’t treated them well. And there’s a wonderful irony in the fact that the buffalo that provided the seed stock came from the largest city in North America, from Bronx Zoo. I mean, you cannot make this up. And that’s why I think it’s really important to tell these individual stories and watch the process.

We tend to, in our current media, make everything binary. There’s nothing binary in nature, right? This idea of good and bad, left and right, young and old, rich and poor, male and female. All of this doesn’t exist. And so what you see, if you do rich and full portraits, is that everybody’s moving, everybody’s changing, everybody’s evolving or devolving. But you’ve got this kind of movement and can begin to capture it. And then you begin to see things like the giant sequoias of the redwoods bearing witness to this human dynamic. And, of course, the buffalo is doing it as well. You look in the eyes of a buffalo; there’s another new herd in New Hampshire that I had the privilege of being with a couple of weeks ago, and they’re startling in their consciousness. I don’t know any other way to put it. You look in their eyes, and it’s like they’ve seen … I sort of wanted to yield to other human perspectives, but also to the animal perspective. Our writer, Dayton Duncan, did a magnificent job on the script. And Julie Dunfey and Julianna [Brannum] helped us tell this important story.

Mongabay: It’s a bit of a departure for you. It’s the first time an animal has been the focus of one of your films.

Ken Burns: Yeah, we were talking about it for years as we were gearing up for a biography of an animal, which was different, but at the same time, we do biographies; it seemed important to try to extend to the natural world. But of course, very early on, we realized that, as Dayton says on camera at the beginning of the film, this will touch on all aspects of our history. And most notably, the relationship with the Native people with that 12,000 years of experience. One woman, Salish Indian Germaine White, says to us that you could think of that 12,000 years as a 24-hour clock. Columbus comes at 11:28 p.m. And Lewis and Clark come at a quarter to midnight. The rest of the story, the history of the US, is just a drop in the bucket to the timespan that Native peoples have coexisted with this animal and sustainably related to it, which is the keyword.

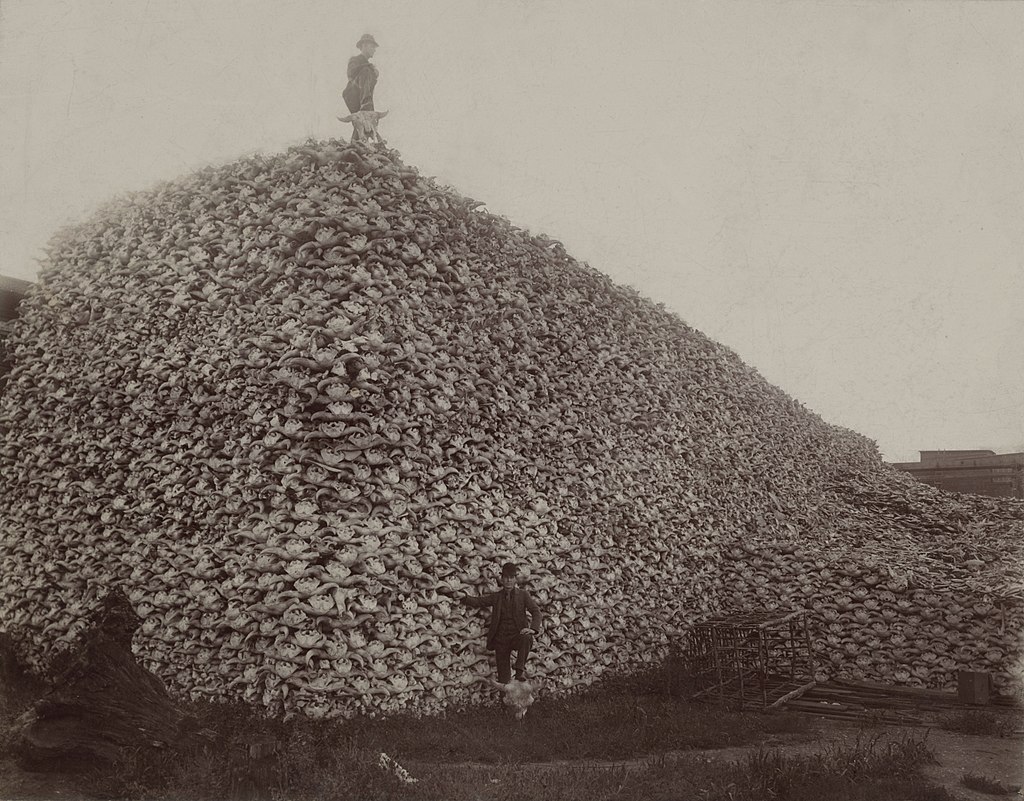

Mongabay: There are so many striking scenes and images in this film. As you said, the migration of the buffalo from Bronx Zoo back to the West is incredible. Also, there are haunting images, such as the image of a man standing on a mountain of buffalo skulls and bones near the railroad. That stuck with me.

Ken Burns: There’s an interesting thing, which is we kill them for their tongues, and we kill them for their hides, leaving everything else to rot, just anathema to the Native use of it. And then, as someone comments in the film, you know, we suddenly found out that the bones that had been bleaching for a couple of decades had value and, in fact, in the end, had more value than anything else. The largest industry was the Detroit Carbon Works, which was grinding these bones. Someone said in the film that it’s like cleaning up a crime scene. We left them to rot there. And the stench was horrific. We also laced some of the carcasses with strychnine. So we’re also killing bald eagles, our national bird, wolves, coyotes, and the predators swarming around the carcasses. It’s just a horrific and thoughtless, incredibly violent act that took place.

Mongabay: Your films tackle some incredibly difficult stories like the Holocaust and the Vietnam War, and now a massacre of a species. How do you and your staff tend to your mental health when you’re facing this type of subject matter, day after day, sometimes year after year? I know many of our readers are in these conservation fields and facing difficult existential things day in and day out.

Ken Burns: I think that’s our job as human beings. I don’t want to soft-pedal and say something unique, some strength to filmmakers, or whatever. It’s tough. But to understand who we are is to understand a very, very dark side of us as well as incredibly positive things. When the Civil War series we made came out in 1990, I said, we’re not going to do any more films on war. It just took too much. And in fact, the Civil War soldiers, both north and south, when they’d been in combat, we’d say they’d seen the elephants, I presume, the most exotic thing you could think of, and combat was unlike anything else, and still is, to this day — you can ask a Ukrainian soldier. But I learned that a thousand veterans of the Second World War were dying each day towards the end of the ’90s. And that lots of our graduating high school students — an unacceptably large number — thought we fought with the Germans against the Russians in the Second World War. And I just, oh my goodness. So we’re diving back in. And before the ink was dry on that project, I decided to do Vietnam, which took 10 and a half years. And before the ink was dry on that project, I decided to do the American Revolution, which is a god-awful, bloody civil war. And that’s because, you know, you have to steel yourself. You have to be prepared to tell the good and the bad of it.

There’s a woman who teaches American history in Maryland, and she’s born in Germany, and in all of her arguments about limiting history and not upsetting our children she says, “I was taught our history, and I’m not traumatized. You know, you have to know this stuff. And you know, the people who are our saviors, our liberators who made us adopt a democratic system, who insisted that our education system never flinch at telling the story — it was you. Now, you’re trying to limit the kind of history.” I think it’s really important for all of us not to shield ourselves from the facts of our past, which are glorious in many ways. I could stop and make an argument for why the United States government, which has made a huge mess of things a lot of times, is the greatest force of good in all of human history. And I can start listing stuff. I don’t have the time to go through that. You know, our national parks are America’s best idea. But you also have to look at everything. You have to lift the carpet, sweep out some dirt, and say, yes, this is also who we are.

[Thomas] Jefferson, when he wrote the Declaration of Independence, said, “All experience has shown that mankind is disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable.” You know, it’s 18th-century prose sounds like it’s an excess. Still, he’s saying all of human history up till now has been authoritarian. And people are willing to live under that. And we’re going to start something new, and it will be hard. And it’s shown us, particularly today, when that form is threatened as it’s never been threatened before — not in the Civil War, not the depression, not the Second World War — that we have to have a kind of deep courage in every aspect of ourselves. And then doing that is in itself mental health, right? If you don’t look at the Holocaust, then what are you pretending? It didn’t exist, as too many people believe? Or that you don’t want to be upset by something as so many other people sometimes on the other side of the political coin feel it’s not about that. You know, none of us get out of here alive. Yeah, period. And so we have to wrestle with the complexities of our past. And that includes really, really good stuff and really, really bad stuff.

Mongabay: The Earth is facing a lot of challenges right now, including this period of mass extinction. There are a lot of species now that are down to fewer than 1,000 individuals as the buffalo once were. What do you think we can learn from the story of the buffalo? What do we take with us into the conservation movement? In what way is this an American story but also a universal story?

Ken Burns: When we began this, I thought that this parable of de-extinction would be helpful in the face of climate change, where we are seeing mass extinctions. We do have many, many species, including megafauna, on the brink of extinction. And maybe this shows you some things and shows you lots of things, as you’re talking about. The fragility of the planet really touches me. I’m a grandfather, and I want my grandchildren to have the same opportunities that I did. And that is going to require some wholesale fundamental changes on our part. And it begins with each individual. And so I think the story of the buffalo is about individual isolated moments as you brought up of people, families, saving some bison, and then collectively doing things. I like to say that I’ve made films about the U.S., but I’ve also made films about us. All of the intimacy of the lowercase two-letter plural pronoun, all of the intimacy of us and we, and our, and all of the majesty and the complexity and the contradiction and controversy of the U.S. go hand in hand.

I think that the buffalo can remind us, let’s just say, that we need to yield to other perspectives. Eighty-plus tribes are involved in the Intertribal Buffalo Council, which is beginning to manage their own herds in tribes that haven’t seen a buffalo in 200 years. Julianna Brannum, our consulting producer, made this lovely film that will be broadcast around the same time as our documentary, called Homecoming. And it’s talking about the work of Jason Baldes and Wind River in Wyoming, a Native American, who is taking buffalo and repatriating them to the Menominee, for example, in Wisconsin. And to see their faces, people who have had this break of 150, 200 or 250 years since buffalo were a frequent companion in their life’s journey — to see them reacquire just some sort of deep archetypal memory, it’s so healing.

I think we’ve got to understand that our addressing of climate change is going to come in lots of forms. There’ll be scientific dimensions, there’ll be political dimensions, there’ll be limitations and regulations on what we do if we’re going to survive. But there will also be human and spiritual dynamics and dimensions to this that we cannot ignore if we are going to survive as well.

Mongabay: Is there anything else you want to add while we’re here together, or that you feel is as important to say about this film or your process?

Ken Burns: I can let on that there was a bit of a discussion in the editing room that we shouldn’t begin with Lewis and Clark, where the film begins. But we should begin with Native peoples. I said, Yes, yes, we will. But the prologue tells you an important thing: these Americans saw the number of bison that were beyond count, waiting for hours for herds to pass by, and then less than a century later, other expeditions couldn’t find one. That’s the goalposts of the basic story we’re going to tell. And then we’ll back up and see, for the first 20 minutes of the film, a Native American story in every single dimension across many tribes and tell the story of how horses changed the life ways of many agricultural tribes. To move across great distances with horses and how that impacted them, and then the market pressures that came from delivering buffalo and the invasion after the Civil War that decimated entire tribes, which was just for a buck, you know, just to make money.

Mongabay: And are you personally feeling hopeful?

Ken Burns: I am. You know it’s important to understand that a lot of those 300,000 buffalo are in feedlots. But more than 20,000 are in Native hands more than 20,000 are in federal hands. There are lots of NGOs that are trying to create habitat and expand habitat for buffalo. And you know, one of the most familiar American tunes is “Home on the Range,” right? And it ought to be our responsibility to make sure there’s a place where the buffalo roam and the deer and the antelope play.

Liz Kimbrough is a staff writer for Mongabay and holds a Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from Tulane University where she studied the microbiomes of trees. View more of her reporting here.

Learn more about Ken Burns’s creative process here at the Pew Charitable Trust’s website.

Read more about buffalo conservation by Indigenous communities:

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.