- Malaysia has blamed forest fires in neighboring Indonesia of causing smoke that has sent air quality levels to unhealthy levels across much of the country.

- Air quality in Kuala Lumpur and other parts of Malaysia have worsened in recent days, with more than a dozen regions recording unhealthy air quality.

- Indonesian officials have denied that fires in their jurisdiction are to blame, and accused their Malaysian counterparts of misreading the data.

- Indonesia dismissed that same source of data in 2019, however, when fires in Sumatra and Borneo also spread to Malaysia and Singapore.

JAKARTA — A diplomatic spat has once again flared up between Southeast Asian neighbors Indonesia and Malaysia, sparked by smoke from forest fires in the former that have reportedly crossed over into the latter.

Air quality in parts of Malaysia have worsened in recent days, with the national environmental department recording unhealthy air quality in 12 areas of Peninsular Malaysia on Sept. 29. By Oct. 2, the number of areas with unhealthy air quality had increased to 15, with the capital, Kuala Lumpur, hit hardest.

The Malaysian government has attributed the worsening air quality to the numerous fires currently burning in the Indonesian territories of Sumatra and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). Out-of-control fire is a perennial issue for Indonesia, often caused by blazes lit to clear land for agricultural purposes like oil palm and pulpwood plantations.

This year’s fire season is expected to be the worst since 2019, due to unusually scorching weather as a result of an El Niño system.

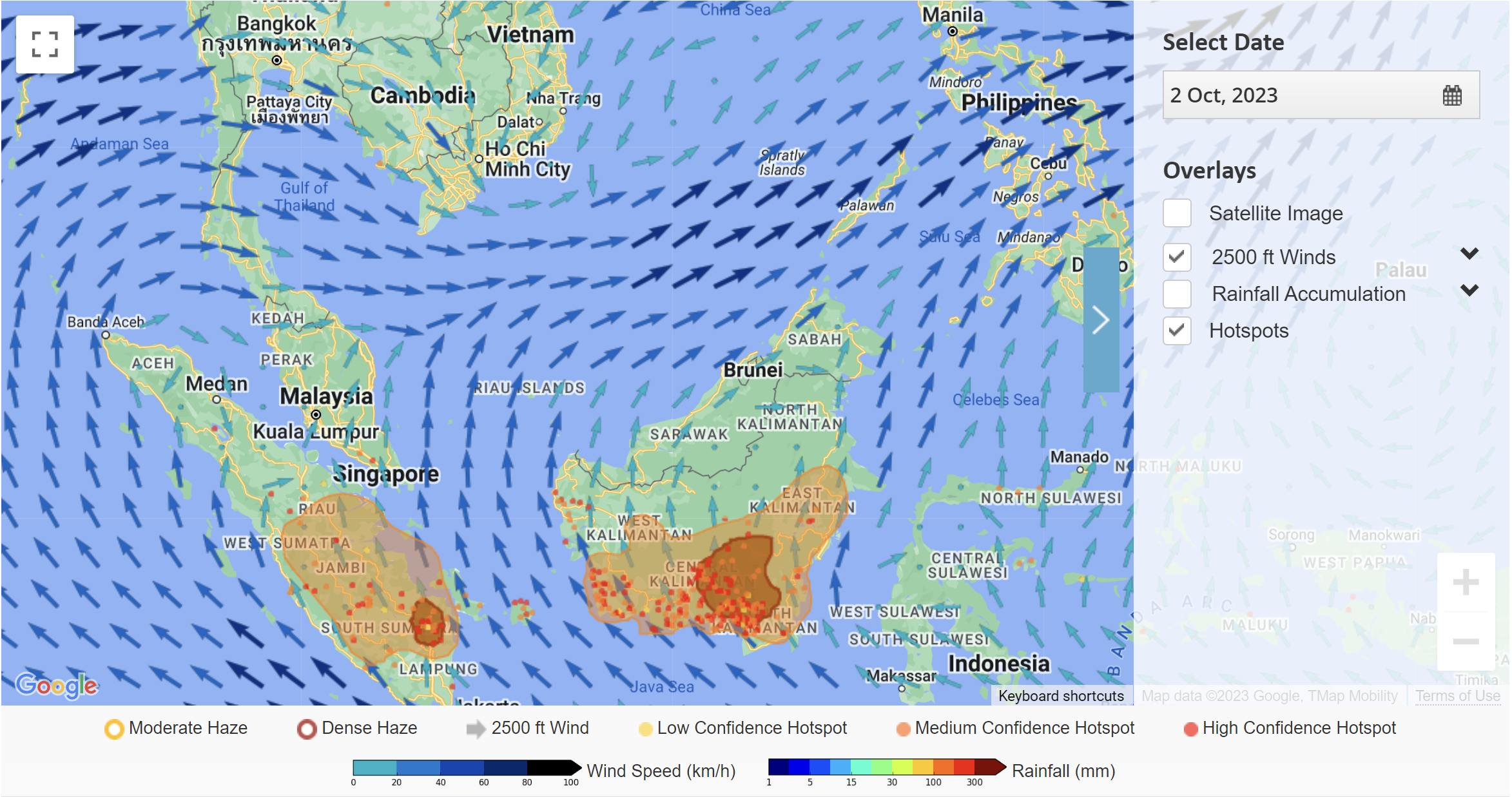

“Forest fires in southern Sumatra and central and southern Kalimantan have resulted in transboundary haze that increases the readings of Air Pollutant Index on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and in western Sarawak [in Malaysian Borneo],” Wan Abdul Latiff Wan Jaffar, director-general of the Department of Environment, said in a statement on Sept. 29.

Latiff cited data from the Singapore-based ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre (ASMC), a regional collaboration between member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations that monitors haze, among other meteorological observations.

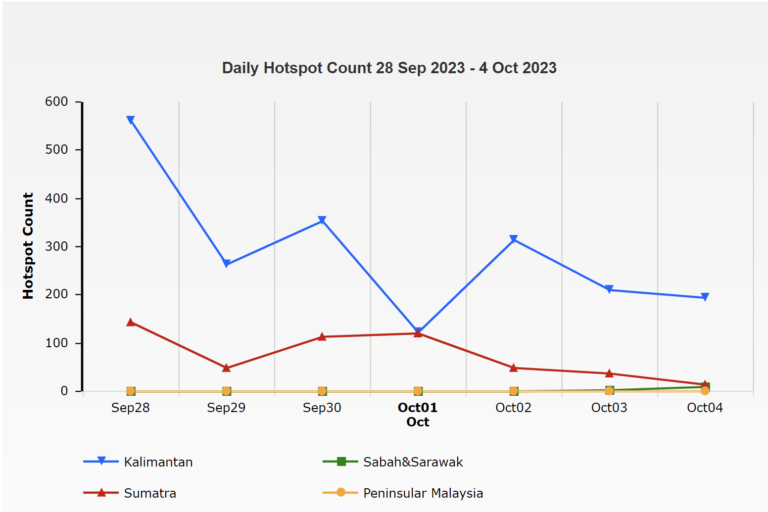

The ASMC uses data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s NOAA-20 satellite, which showed a massive disparity between the number of fire hotspots in Indonesia and Malaysia.

On Sept. 29, the ASMC detected 49 hotspots in Sumatra, 263 in Kalimantan, and none in Malaysia. On Sept. 30, these had increased to 113 and 353 hotspots in Sumatra and Kalimantan respectively, and still none in Malaysia.

Following the deteriorating air quality in Malaysia, the country’s environment minister, Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, has sent a letter to his counterpart in Jakarta, Siti Nurbaya Bakar, requesting for a coordination to resolve the transboundary haze issue.

“We submitted our letter to inform the Indonesian government and urging them to hopefully take action on the matter,” he said in an interview on Oct. 4. “We cannot keep going back to having haze as something normal.”

He said on Oct. 5 that he had not yet received a response from Siti.

Muhammad Helmi Abdullah, director-general of the Malaysian Meteorological Department (MetMalaysia), said the southern states of Peninsular Malaysia should brace from haze coming from fires in Sumatra over the next few days, while Malaysian Borneo would be hit by haze from Kalimantan.

“The trajectory of the haze from Kalimantan is expected to affect Kuching, Serian and Samarahan (in Sarawak) during the forecast period,” Helmi said as quoted by the New Straits Times on Oct. 1.

According to the ASMC, dense smoke plumes from fires in Sumatra have been blown northwest by prevailing winds. Crucially, however, the ASMC stopped short of saying that smoke from Sumatra has reached Malaysia.

Officials in Indonesia have seized on this to deny that they’re to blame for the poor air quality in Malaysia. In Jakarta, the environment minister, Siti, said in a statement on Oct. 2 that continuous monitoring had shown “there’s no transboundary haze reaching Malaysia.”

She said monitoring by both the ASMC and Indonesia’s meteorological agency, the BMKG, didn’t find any transboundary haze from Sept. 28-30.

“So it’s clear, both [the ASMC and the BMKG] said there’s no transboundary haze,” she said.

Siti also suggested her Malaysian counterpart had a poor understanding of the ASMC data by conflating hotspots detected, which don’t always correspond to fires, with firespots, which do.

“Don’t they know the difference between hotspots and firespots? If [you] don’t know exactly, don’t talk carelessly,” she said as quoted by AFP on Sept. 30.

Ailish Graham, an air pollution researcher at the University of Leeds, said it’s possible that haze from the fires in Indonesia has been transported to Malaysia under favourable winds, like what happened in 2015 when there were large fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan.

However, based on the data available, it is not possible to conclusively say if smoke from Indonesia is contributing to the recent worsening of air quality in Peninsular Malaysia, she said.

“[…] it is necessary to run an atmospheric chemistry transport model with and without fires in order to be sure of this,” Graham told Mongabay.

Bilateral blame game

The Indonesian minister’s remarks, relying on ASMC data to deflect criticism, are in stark contrast to 2019, the last significant fire season in the region, when she dismissed the same source of data.

That year, the countries also traded barbs over blame for haze. The fires in Indonesia burned 1.64 million hectares (4.05 million acres) of land and caused a public health crisis due to the toxic smog from the fires. And while Siti acknowledged at the time that Kuala Lumpur was also hit by smoke, she said it was generated in Malaysia and didn’t come from Indonesia.

Malaysia’s environment minister at the time, Yeo Bee Yin, said the facts showed otherwise, and pointed to ASMC data showing more than 1,000 hotspots in Indonesia during the peak of the fire season, against just five in Malaysia. Yeo also cited ASMC maps showing the wind direction during the fire episode, and how haze from Sumatra and Kalimantan reached parts of Malaysia.

In 2015, another period of severe burning across Sumatra and Kalimantan, Indonesia’s vice president at the time accused neighboring Malaysia and Singapore of ungrateful for the fresh air that Indonesia’s forests provided them outside the haze season.

“For 11 months, they enjoyed nice air from Indonesia and they never thanked us,” Jusuf Kalla said. “They have suffered because of the haze for one month and they get upset.”

Helena Varkkey, an associate professor of environmental politics at Malaya University in Kuala Lumpur, said the blame game boils down to national pride.

“Complaints and requests from affected countries to Indonesia to control its fires often dissolve into finger-pointing as each country blames the other’s plantations for causing the fires,” she wrote in an op-ed in 2022.

Need for anti-haze laws

Since haze is transboundary in nature, the problem can’t be addressed by any individual country, Varkkey said.

Malaysian environment minister, Nik Nazmi, called for ASEAN, as a region bloc, to work together to prevent the yearly haze.

“I hope that every country will be able to be open in order to find a solution because the damage to the economy, to tourism, but especially to health, is immense from the haze,” he said.

Groups such as Greenpeace Southeast Asia, meanwhile, are calling for governments in the region to enact transboundary haze laws in their respective countries.

ASEAN, as a region bloc, has since 2002 had an agreement on transboundary haze pollution in place, which all ASEAN member states have signed. To date, however, only Singapore has ratified it by enacting its own transboundary haze pollution act (THPA).

This law “empowers its government to punish perpetrators that add to the haze domestically and gives individuals the power to take legal action against private companies abroad,” said Heng Kiah Chun, regional campaign strategist at Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

Singapore has since used the law to sue Indonesian company Asia Pulp & Paper, one of the world’s biggest paper producers, and a group of smaller firms in 2015 after one of the most severe periods of haze ever recorded. The government’s case against APP is still pending.

Malaysia, which has significant businesses in industries that are responsible for fires in the region, should follow suite, Heng said.

“Enacting a domestic transboundary haze act is necessary to act as a deterrent, especially as there are bad apples in the industry,” he said. “It can provide legal grounds for each country to institutionalize checks and balances to ensure their own companies operate responsibly.”

Malaysian interests own up to 30% of Indonesian palm-oil plantations. Malaysia initially planned to introduce legislation on domestic transboundary haze in 2019, but this was shelved after a change in government.

“A THPA would give us the necessary legal authority to hold at least Malaysian companies that are operating outside of Malaysia responsible for their unsustainable practices,” Heng said.

Nik Nazmi said Malaysia was still “seriously” considering a law similar to Singapore that punishes companies liable for air pollution. However, there were questions on whether Malaysia could prosecute polluters that are based overseas, he added.

Banner image: Haze rising from an oil palm plantation and forest in Riau province. Image by Rhett A. Butler / Mongabay.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.