- Fishing communities in Indonesia’s Kei Islands support the idea of a marine protected area to safeguard their main source of livelihood from unsustainable fishing and climate change impacts.

- That’s the finding of a new study by local researchers, who found that the majority of respondents said they were also willing to contribute a token annual payment for the upkeep of such an MPA.

- The researchers have proposed the MPA to the local government and council, and say they hope that if it’s accepted, it could serve as a template for other MPAs in the region.

- The waters around the Kei Islands are blessed with some of the richest fish stocks in Indonesia, but destructive fishing practices and the impacts of climate change are threatening the age-old fishing tradition here.

JAKARTA — Communities on an island in eastern Indonesia increasingly support the idea of a marine protected area in an effort to reverse declining fish stocks in their waters.

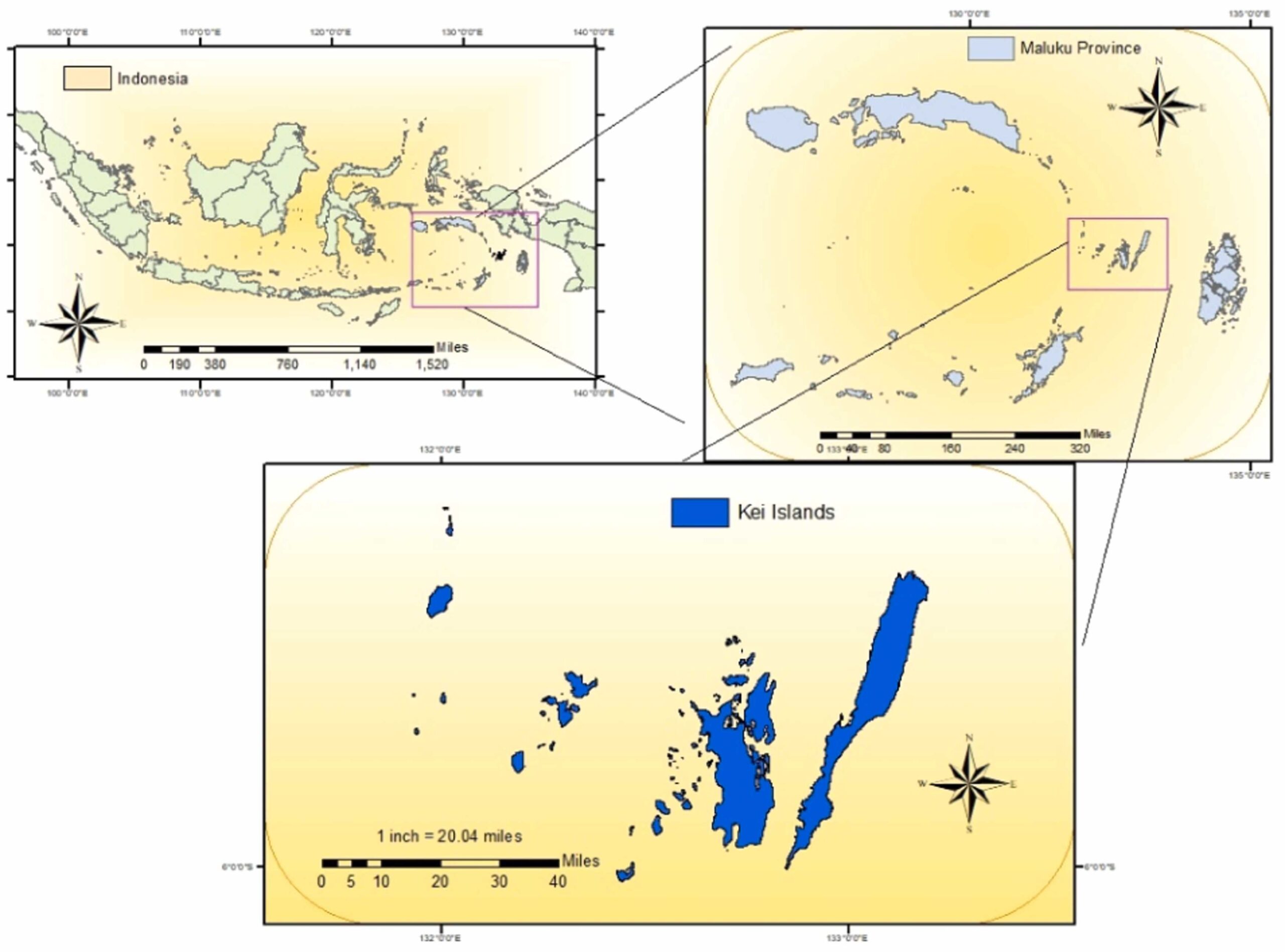

A new survey from Indonesia’s Kei Islands in Maluku province found that communities there approve of an MPA covering the southern part of their coast. They said it would decrease the impacts of destructive fishing and climate change that they’ve experienced in recent years, according to the study by a group of Indonesian researchers published Sept. 16 in the journal Marine Policy.

“When I was between elementary and middle school, I could just fish right in front of my house as it’s facing the beach. Nowadays, no more fish are around very close, so you really have to go out far,” study lead author Wellem Anselmus Teniwut, a researcher at Tual State Fisheries Polytechnic, told Mongabay.

The Kei Islands are peppered across 1,438 square kilometers (555 square miles) of the western Pacific, and are blessed with some of the richest fishing grounds in Indonesia’s extensive waters. The tiny archipelago, part of the legendary Spice Islands that drew waves of European sailors and traders, is also at the center of the Pacific Coral Triangle, home to the highest density of marine biodiversity anywhere on the planet.

“The worst thing is that when we were kids, there would be storms and waves and the water never flooded into our village, but now that’s changed,” Wellem said. “We’ve become scared, we’d have to get up in the middle of the night and get ready to rescue our belongings just in case our houses would flood.”

These extreme environmental changes, Wellem said, inspired him and his team to investigate the causes and find the solutions. They started in 2018 by conducting interviews with locals across the Kei Islands, and in 2020 came to the conclusion that conservation efforts had to be implemented in the region. But Wellem said the majority of people at the time rejected the conservation proposal if it meant full restrictions on fishing. For many, this is the main form of livelihood, earning an average of 1.5 million rupiah ($96) per month, or half of the national average monthly income.

Approximately 40% of the sea area in this region of the Malukus is dominated by fishing grounds split between the two subdistricts of Kei Kecil Barat and Manyeuw. While fishing is the top source of income for many households in Kei, experts have noted declining interest in the sector among young people here due to the fact that marine- and fishing-related businesses generate much less than other jobs.

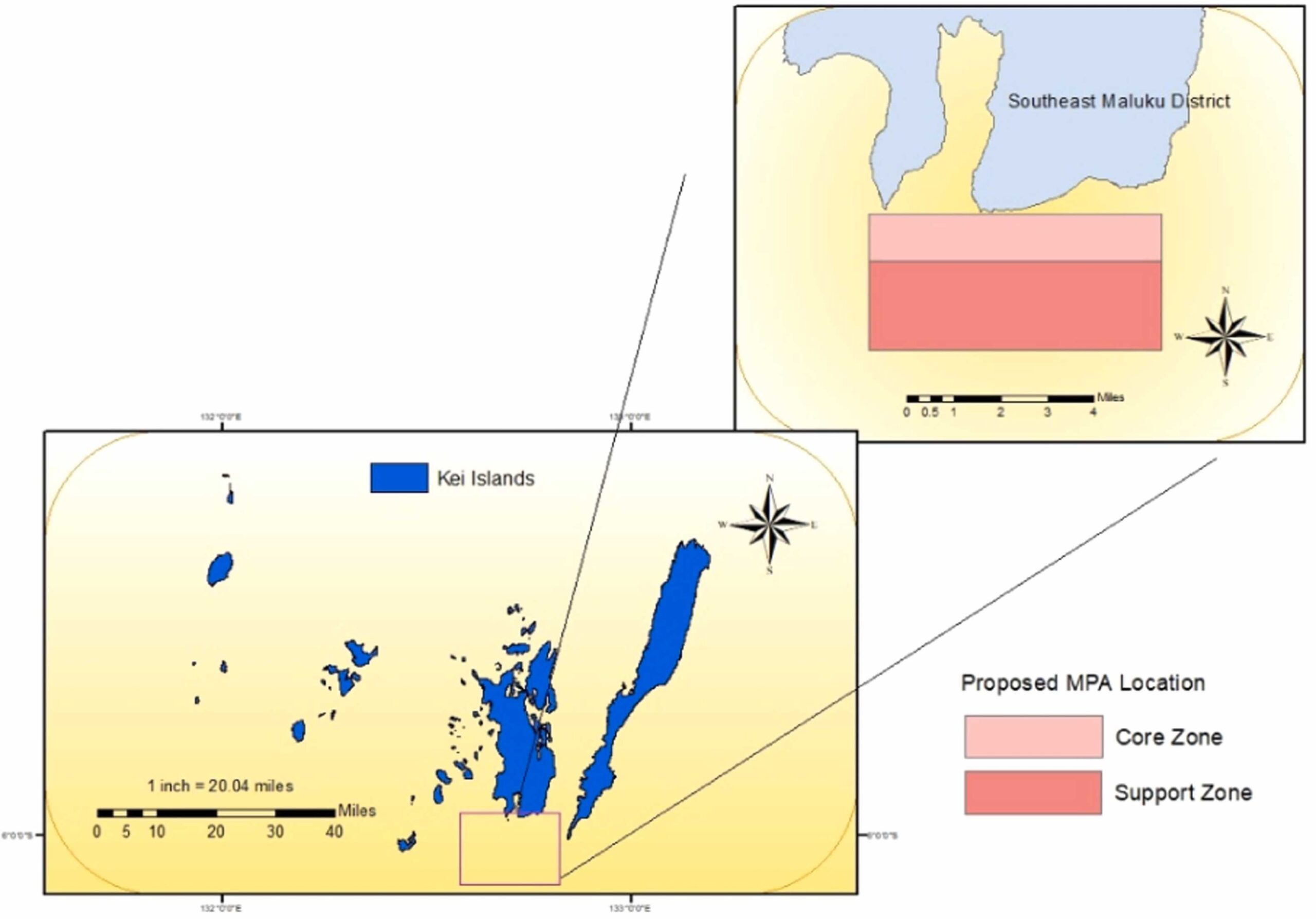

That led Wellem and his team to conduct another survey in 2021, combining local wisdom and modern science to propose a conservation plan that the communities said they accepted and even agreed to take part in funding the management. This would entail creating an MPA spanning about 12 km2 (4.6 mi2) off the southern coast of the Kei Islands, with each household contributing 20,000-50,000 rupiah ($1.30-$3.20) per year for maintenance.

“We have also put our findings in a draft and proposed it as a bylaw to the Southeast Maluku district office and council. We’ve had some discussions, but nothing has been decided. Maybe it’s because they’re now focused on the upcoming election cycle,” Wellem said.

Wellem said the proposed MPA could serve as a pilot project for two more sites across the region. He said expected the establishment of an MPA would also translate into increased monitoring by local marine authorities, thereby reducing threats of illegal and destructive fishing and coastal exploitation.

“As our effort continues, we hope to be able to develop a few other sites, and that the fishes in Kei won’t swim further away because the environment is degrading,” Wellem said.

Indonesia plans to expand protection of its seas to cover 10% of its total waters by 2030, before tripling that proportion it by 2045. The country currently has 284,000 km2 (110,000 mi2) of marine area under protection. The move is part of the country’s contribution to the global “30 by 30” conservation goal, which aims to protect 30% of the world’s seas and lands by 2030.

Basten Gokkon is a senior staff writer for Indonesia at Mongabay. Find him on 𝕏 @bgokkon.

See related:

Four new MPAs in Maluku boost Indonesia’s bid to protect its seas

Citation:

Teniwut, W. A., Hamid, S. K., Teniwut, R. M. K., Renhoran, M., & Pratama, C. D. (2023). Do coastal communities in small islands value marine resources through marine protected areas?: Evidence from Kei Islands Indonesia with choice modelling. Marine Policy, 157, 105838. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105838

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.